PEP: Everything You Need to Know About Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

Introduction

Post-exposure prophylaxis, commonly known as PEP, is one of the most important emergency HIV prevention tools available today. PEP involves taking a 28-day course of HIV medicines after a possible exposure to prevent HIV infection. It is not meant for regular use but is highly effective when taken correctly and within the recommended time frame.

This comprehensive guide explains what PEP is, who should use it, how effective it is, possible side effects, and what steps to take after completing treatment.

What is PEP?

PEP stands for post-exposure prophylaxis. The term “prophylaxis” refers to preventing or controlling the spread of infection or disease. In the case of HIV, PEP involves taking antiretroviral medicines within 72 hours (3 days) of a potential exposure.

Key points to remember about PEP:

- PEP must be started within 72 hours of exposure. The sooner, the better—every hour counts.

- PEP is taken daily for 28 days.

- PEP should only be used in emergencies, not as a regular prevention method.

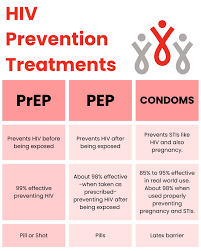

- PEP is different from PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), which is taken before exposure by people at ongoing risk of HIV.

While PrEP protects people on a long-term basis, PEP is designed for urgent situations after a potential HIV exposure.

Who Should Consider Taking PEP?

PEP may be prescribed to people who do not have HIV or who are unsure of their HIV status and have had a possible exposure within the last 72 hours. Common situations where PEP may be necessary include:

1. Sexual Exposure

- Having unprotected vaginal or anal sex with someone who may have HIV.

- A condom breaking or slipping during intercourse with a partner of unknown HIV status.

2. Needle Sharing

- Sharing needles, syringes, or other equipment to inject drugs.

- Accidental needle-stick injuries in healthcare or community settings.

3. Sexual Assault

- Survivors of sexual assault may be at risk and should seek immediate medical care to determine if PEP is needed.

4. Occupational Exposure

- Healthcare workers exposed to HIV-positive blood or body fluids through accidental injury (e.g., needle sticks, splashes into mucous membranes).

If you think you have been exposed to HIV, seek medical help immediately. Emergency rooms, clinics, or healthcare providers can prescribe PEP. Do not wait—acting fast is essential.

When Should PEP Be Started?

The timing of PEP is crucial for its success. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

- PEP must be started within 72 hours of a possible HIV exposure.

- Starting treatment as soon as possible increases effectiveness—every hour counts.

- PEP is not likely to prevent HIV if started more than 72 hours after exposure.

Once prescribed, you must take the medicines daily for 28 days without missing doses.

What HIV Medicines Are Used for PEP?

The CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO) provide guidelines on which HIV medicines should be used for PEP. The medicines usually include a combination of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs).

The specific regimen may vary depending on:

- Age (adults, adolescents, children)

- Pregnancy status

- Existing health conditions (such as kidney problems)

Healthcare providers will determine the safest and most effective combination for each individual.

How Effective is PEP?

PEP is highly effective when taken correctly, but it does not provide 100% protection. Effectiveness depends on:

- Starting quickly: The sooner PEP is taken after exposure, the better.

- Completing the 28-day course: Skipping doses or stopping early reduces effectiveness.

- Avoiding additional exposures: Engaging in unprotected sex or sharing needles while on PEP reduces its success rate.

Research shows that PEP can reduce the risk of HIV infection by more than 80%, and effectiveness is even higher when adherence is excellent. However, PEP is not a substitute for regular prevention methods such as condoms or PrEP.

PEP vs. PrEP: What’s the Difference?

Both PEP and PrEP involve HIV medicines, but they serve different purposes.

- PEP (Post-Exposure Prophylaxis): Taken after a possible HIV exposure. It is an emergency measure used for 28 days.

- PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis): Taken before possible exposure, usually as a daily pill or injection every two months. It is for people at ongoing risk of HIV.

PEP should not be used as a replacement for PrEP. If you find yourself frequently at risk of HIV exposure, talk to your healthcare provider about starting PrEP for long-term protection.

Side Effects of PEP

Like all medicines, PEP may cause side effects, although not everyone experiences them.

Common Side Effects

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

- Headaches

- Tiredness

These are usually mild and manageable with medical support.

Rare but Serious Side Effects

- Liver problems

- Lactic acidosis (a buildup of acid in the blood)

If you experience severe or persistent side effects, contact your healthcare provider immediately. Most people are able to complete the 28-day course without major issues.

What to Do After Taking PEP

Completing PEP is only one part of HIV prevention. What you do afterward matters for your health and future protection.

1. HIV Testing

- You will be tested for HIV at the end of the 28-day course.

- Additional follow-up testing may be recommended at 3 months and 6 months after exposure.

2. Consider Long-Term Prevention

If you test negative for HIV, discuss long-term prevention options with your healthcare provider:

- PrEP for ongoing protection.

- Consistent condom use during sex.

- Avoiding needle sharing if you inject drugs.

3. Next Steps if You Test Positive

If you test positive for HIV after taking PEP:

- Additional testing (lab confirmation) will be required.

- You will be connected to HIV care and treatment with antiretroviral therapy (ART).

- Early treatment helps maintain good health and prevents transmitting HIV to others.

Limitations of PEP

While PEP is a powerful prevention tool, it has limitations:

- It must be started within 72 hours of exposure.

- It requires strict adherence to the 28-day course.

- It does not protect against other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

- It is not a replacement for regular HIV prevention methods like condoms or PrEP.

For this reason, PEP should be seen as an emergency option, not a long-term prevention strategy.

Key Takeaways About PEP

- PEP (Post-Exposure Prophylaxis) is a 28-day course of HIV medicines taken after a possible exposure.

- It must be started within 72 hours, and sooner is better.

- PEP is effective but not 100%—success depends on adherence and avoiding further risk.

- Common side effects are mild, but rare serious side effects require medical attention.

- After completing PEP, HIV testing and long-term prevention strategies like PrEP should be considered.

Final Thoughts

PEP is a life-saving tool that can dramatically reduce the risk of HIV infection if started promptly and taken as prescribed. It is designed for emergencies, not everyday use, and should always be combined with other prevention methods such as condoms, PrEP, and safe practices.

If you believe you have been exposed to HIV, do not wait—seek medical attention immediately to discuss whether PEP is right for you. Acting quickly can make the difference between preventing HIV and facing a lifelong infection.